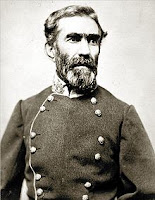

On this date in 1863, Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill is given command of Hardee’s former corps, which has been under the temporary command of Gen. Patrick Cleburne, since on the 14th, Hardee had been ordered to join Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army in Jackson, Mississippi. Hill will officially assume command on the 24th.

A Southern scholar and a father of 9, Hill was also known as an austere and aggressive leader. He was a devout Christian, with a dry and sometimes sarcastic sense of humor. He was a brother-in-law to Stonewall Jackson, and a close friend to both James Longstreet and Joseph E. Johnston, but disagreements with both Robert E. Lee and Braxton Bragg eventually cost Hill favor with President Jefferson Davis. Although Hill was well respected for his his military ability, he was underutilized by the end of the Civil War due to politics.

A Southern scholar and a father of 9, Hill was also known as an austere and aggressive leader. He was a devout Christian, with a dry and sometimes sarcastic sense of humor. He was a brother-in-law to Stonewall Jackson, and a close friend to both James Longstreet and Joseph E. Johnston, but disagreements with both Robert E. Lee and Braxton Bragg eventually cost Hill favor with President Jefferson Davis. Although Hill was well respected for his his military ability, he was underutilized by the end of the Civil War due to politics.

D.H. Hill, descended from patriots in the War for Independence, graduated from the the United States Military Academy in 1842, ranking 28 out of 56 cadets, and was appointed to the 1st United States Artillery. He distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War and was promoted to captain for bravery at the Battle of Contreras and Churubusco, and later promoted to major for bravery at the Battle of Chapultepec.

In 1849, Hill resigned his commission to become a professor of mathematics at Washington College (now Washington and Lee University). While at the college he wrote a textbook, Elements of Algebra. In 1854, he joined the faculty of Davidson College in North Carolina, and in 1859, was made superintendent of the North Carolina Military Institute of Charlotte.

As the War Between the States neared, Hill, like many other Southerners, believed that the Confederacy represented a second American attempt to build a free nation, just as legitimate as its first effort in 1776. When war finally came, Hill joined the Southern cause as a colonel of the 1st North Carolina Infantry, leading his regiment in victory at the Battle of Big Bethel in Virginia in 1861. He was soon promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of troops in the Richmond area. By the spring of 1862, he was a major general and division commander in the Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee. He participated in the Yorktown and Williamsburg operations that started the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, leading a division with great distinction in the Battle of Seven Pines and the Seven Days Battle.

As the War Between the States neared, Hill, like many other Southerners, believed that the Confederacy represented a second American attempt to build a free nation, just as legitimate as its first effort in 1776. When war finally came, Hill joined the Southern cause as a colonel of the 1st North Carolina Infantry, leading his regiment in victory at the Battle of Big Bethel in Virginia in 1861. He was soon promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of troops in the Richmond area. By the spring of 1862, he was a major general and division commander in the Army of Northern Virginia under Robert E. Lee. He participated in the Yorktown and Williamsburg operations that started the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, leading a division with great distinction in the Battle of Seven Pines and the Seven Days Battle.

In the Maryland Campaign of 1862, Hill led his division at South Mountain, buying Lee's army enough time to concentrate at nearby Sharpsburg. Hill's division saw fierce action in the infamous sunken road ("Bloody Lane") at Antietam. Next, he led his division at the Battle of Fredericksburg. When Robert E. Lee reorganized his army in 1863, however, Hill was passed over as a corps commander. During the Gettysburg Campaign, he led Confederate reserve troops protecting Richmond.

In July of 1863, Hill was appointed lieutenant-general and sent west to command Hardee's Corps, comprised of Cleburne's and Breckinridge's Divisions at Chickamauga. Great Grandfather Nathan Oakes will serve under Gen. Hill in Cleburne's Division throughout the campaign. In the bloody battles that encompassed that struggle, Hill's forces saw some of the heaviest fighting, leading to a Confederate victory. However, afterward, an embittered Hill joined several other generals in condemning Bragg's failure to exploit the victory and destroy Rosecrans's army. President Davis had to come personally to resolve the sharp dispute, but again, he acted in favor of Bragg. The result was another reorganization of the Army of Tennessee, with Hill removed from command. Essentially, Hill was demoted, relegated to the sidelines, although he did command in smaller actions away from the major armies.

Hill was called back to the Army of Tennessee in the closing days of the war. He led a division of Alabamian and South Carolinian brigades against Sherman's army through the Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina, in the last fight of the Army of Tennessee. He surrendered with the rest of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army on April 26, 1865.

In the years after the war Hill returned to academic life, first editing influential magazines, The Land We Love and The Southern Home, each devoted to important Southern subjects. In 1877-1880, he was president of the Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas). In 1885, he was appointed president of the Georgia Military and Agricultural College (now Georgia Military College), serving until August 1889, when he resigned due to failing health brought on by stomach cancer. He died in Charlotte a month later, on September 24, 1889. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill is buried in Davidson College Cemetery, the college where he was Mathematics Chair from 1854-1859.

Sources: Stonewall of the West, Craig L. Symonds; Autumn of Glory, Thomas Lawrence Connelly; Daniel Harvey Hill, Dan L. Morrill; Official Records, Vol. 23, Pt. 3